“There is no great difference between novels and banana bread. They are both just something to do. They are no substitute for love… Love is not something to do, but… something to go through — that must be why it frightens so many of us and why we so often approach it indirectly.”

By Maria Popova

“Whatever inspiration is, it’s born from a continuous I don’t know,” the Polish poet Wisława Szymborska observed in her magnificent Nobel Prize acceptance speech. But a central paradox of making art and making life is that while uncertainty may be the wellspring of our creative vitality — what is best in life and art often comes into being by “making-not-knowing,” in artist Ann Hamilton’s lovely phrase — we are capable of creating only by hedging against the uncertainty with an arsenal of habits and routines that make it feel containable, controllable, workable. We simply cannot cope with the fundamental precariousness of it all. Every artist’s art is their coping mechanism — their makeshift raft for the slipstream of time and uncertainty that is life.

And so: When some cataclysm in the slipstream capsizes the raft, shatters it, leaves us gasping amid the flotsam, ejected from the familiar flow of time — do we sink or sing?

That is what Zadie Smith explores in one of the six symphonic essays from her Intimations (public library) — a slender, splendid book, all of her royalties from which Smith is donating to the Equal Justice Initiative and New York’s COVID-19 emergency relief fund; a book inspired by her first encounter with Marcus Aurelius’s classic Meditations, on which she leaned to steady herself in these staggering times but which failed to make of her a Stoic, driving her, as the world’s gaps and failings drive us restive makers, to make what meets the unmet need, a contemporary counterpart to these ancient private meditations of timeless public resonance. (We cannot, we must not, after all, expect a white male monarch — however penetrating his insight into human nature, whatever the similitudes of that elemental nature across cultures and civilizations — to speak for and to all of humanity across all of time.)

Zadie Smith (Photograph by Dominique Nabokov)

Zadie Smith (Photograph by Dominique Nabokov)

In the third essay, titled “Something to Do,” Smith contemplates the strange and inevitable species of essays in which writers examine their own motives for what they do, that is, examine the pylons of who they are — a genre perhaps not pioneered but popularized by Orwell’s iconic Why I Write and since swelled with specimens by such titans of literature as Joan Didion, David Foster Wallace, and Smith herself. At the bottom of all such self-examination — which spares no maker, whatever the mode and material of their art, be it essays or gardens or equations — is the question of time, the raw material of making, something Marcus Aurelius’s fellow Stoic Seneca took up in his excellent meditation on the existential calculus of time spent, saved, and wasted, concluding that “nothing is ours, except time.”

With an eye to the capitalist commodification of time in a culture of utilitarian busyness, Smith considers how society ordinarily weighs the cultural and temporal responsibility of the artist:

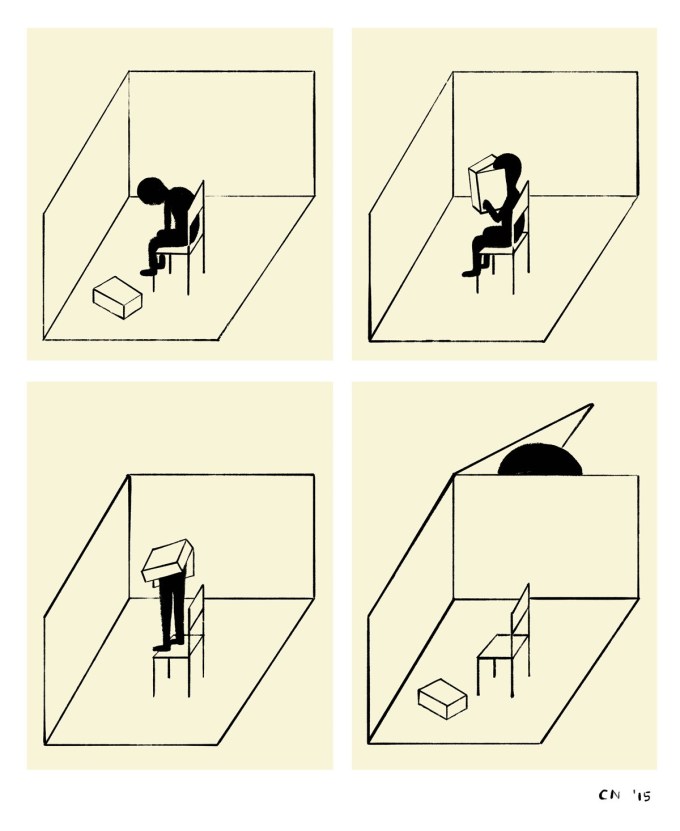

Why did you bake that banana bread? It was something to do… Out of an expanse of time, you carve a little area — that nobody asked you to carve — and you do “something.” But perhaps the difference between the kind of something that I’m used to, and this new culture of doing something, is the moral anxiety that surrounds it. The something that artists have always done is more usually cordoned off from the rest of society, and by mutual agreement this space is considered a sort of charming but basically useless playpen, in which adults get to behave like children — making up stories and drawing pictures and so on — though at least they provide some form of pleasure to serious people, doing actual jobs… As a consequence, art stands in a dubious relation to necessity — and to time itself. It is something to do, yes, but when it is done, and whether it is done at all, is generally considered a question for artists alone. An attempt to connect the artist’s labor with the work of truly laboring people is frequently made but always strikes me as tenuous, with the fundamental dividing line being this question of the clock. Labor is work done by the clock (and paid by it, too). Art takes time and divides it up as art sees fit. It is something to do.

Art by Christoph Niemann from A Velocity of Being: Letters to a Young Reader.

Art by Christoph Niemann from A Velocity of Being: Letters to a Young Reader.

Under such a premise, she observes, artists would seem to be most impervious to the cataclysmic disruption of labor that a global pandemic inflicts upon our species. But that is not what her experience — or my experience, or the experience of any creative person I know — has been. One is reminded of James Baldwin, insisting half a century earlier in his superb essay on the creative process that “a society must assume that it is stable, but the artist must know, and he must let us know, that there is nothing stable under heaven.” Not even time, the artist’s own fulcrum of stability. Smith writes:

It seems it would follow that writers — so familiar with empty time and with being alone — should manage this situation better than most. Instead, in the first week I found out how much of my old life was about hiding from life. Confronted with the problem of life served neat, without distraction or adornment or superstructure, I had almost no idea of what to do with it. Back in the playpen, I carved out meaning by creating artificial deprivations — time, the kind usually provided for people by the real limitations of their real jobs. Things like “a firm place to be at nine a.m. every morning” or a “boss who tells you what to do.” In the absence of these fixed elements, I’d make up hard things to do, or things to abstain from. Artificial limits and so on. Running is what I know. Writing is what I know. Conceiving self-implemented schedules: teaching day, reading day, writing day, repeat. What a dry, sad, small idea of a life. And how exposed it looks, now that the people I love are in the same room to witness the way I do time. The way I’ve done it all my life.

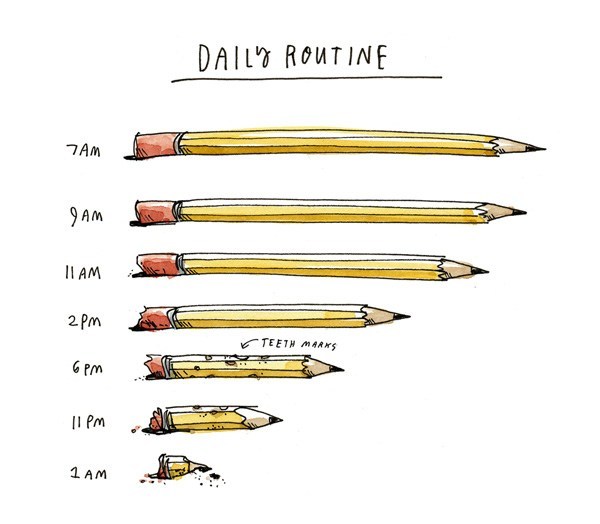

“Artificial limits,” of course, are how we contour and fill our sense of meaning amid the vast, empty boundlessness of being. That is why the artificial limits of those we deem to have meaningful lives — the daily routines of great makers and thinkers — are of such enduring and intoxicating interest to us, why we hunger for the cognitive science of the ideal daily routine.

Art by Wendy MacNaughton for Brain Pickings

Art by Wendy MacNaughton for Brain Pickings

But much of our temporal anguish stems precisely from this artificial contouring of selfhood in the sand of time. We are essentially self-referential timekeeping devices. I noticed, for instance — how could one not? — that this book was published on my birthday. We mark up the year with the same artificial timestamps with which we mark up the hour. What we do with our days, how we itemize them into scheduled rhythms, is another twitch of the same ludicrous, helplessly human impulse — to own time, to turn into private property what may be the only truly public good. Eventually — perhaps in the time-warp of a pandemic, perhaps in that of private grief — something stops us up short and we face the absurdity of such artificiality. Smith recounts her own stumbling stop and the disquieting yet strangely life-affirming realization it made her step into:

At the end of April, in a powerful essay by another writer, Ottessa Moshfegh, I read this line about love: “Without it, life is just ‘doing time.’” I don’t think she intended by this only romantic love, or parental love, or familial love or really any kind of love in particular. At least, I read it in the Platonic sense: Love with a capital L, an ideal form and essential part of the universe — like “Beauty” or the color red — from which all particular examples on earth take their nature. Without this element present, in some form, somewhere in our lives, there really is only time, and there will always be too much of it. Busyness will not disguise its lack.

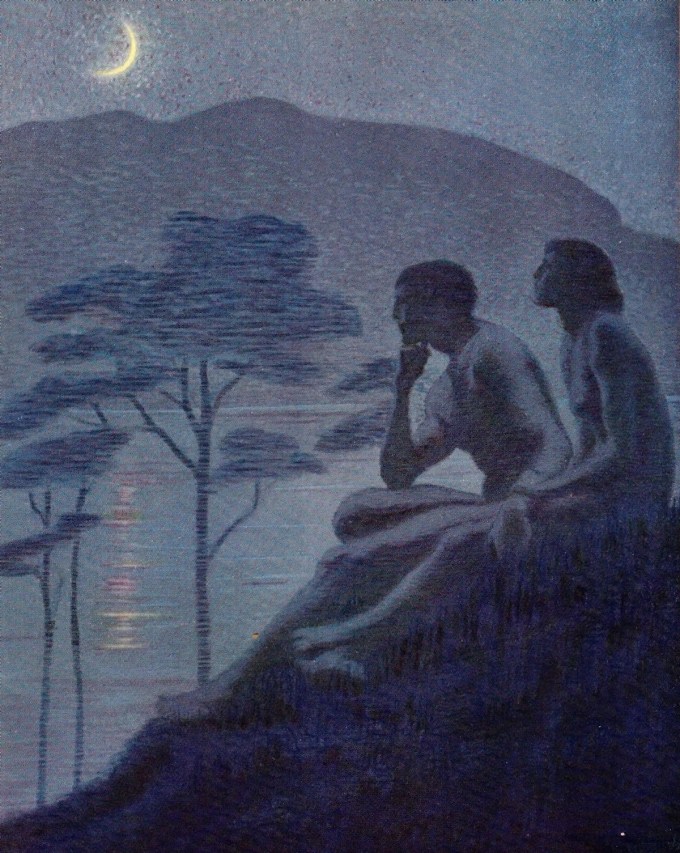

Art by Margaret C. Cook from a rare 1913 English edition of Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass. (Available as a print.)

Art by Margaret C. Cook from a rare 1913 English edition of Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass. (Available as a print.)

Ending where she began, Smith quiets the moral anxiety to make herself at home in that peculiar and inescapable place that makers inhabit by their very nature, the place between compulsion and consecration:

I write because… well, the best I can say for it is it’s a psychological quirk of mine developed in response to whatever personal failings I have. But it can’t ever meaningfully fill the time. There is no great difference between novels and banana bread. They are both just something to do. They are no substitute for love. The difficulties and complications of love — as they exist on the other side of this wall, away from my laptop — is the task that is before me, although task is a poor word for it, for unlike writing, its terms cannot be scheduled, preplanned or determined by me. Love is not something to do, but something to be experienced, and something to go through — that must be why it frightens so many of us and why we so often approach it indirectly. Here is this novel, made with love. Here is this banana bread, made with love. If it weren’t for this habit of indirection, of course, there would be no culture in this world, and very little meaningful pleasure for any of us. Although the most powerful art, it sometimes seems to me, is an experience and a going-through; it is love comprehended by, expressed and enacted through the artwork itself, and for this reason has perhaps been more frequently created by people who feel themselves to be completely alone in this world — and therefore wholly focused on the task at hand — than by those surrounded by “loved ones.” Such art is rare: we can’t all sit cross-legged like Buddhists day and night meditating on ultimate matters. Or I can’t. But I also don’t want to just do time anymore, the way I used to. And yet, in my case, I can’t let it go: old habits die hard. I can’t rid myself of the need to do “something,” to make “something,” to feel that this new expanse of time hasn’t been “wasted.” Still, it’s nice to have company. Watching this manic desire to make or grow or do “something,” that now seems to be consuming everybody, I do feel comforted to discover I’m not the only person on this earth who has no idea what life is for, nor what is to be done with all this time aside from filling it.

Complement this fragment of Smith’s solacing and vitalizing Intimations with Frankenstein author Mary Shelley on the necessary chaos of creativity, Borges’s timeless refutation of time, and Rilke on the lonely patience of creative work, then revisit Smith, writing years ago as if of and to today, on optimism and despair.